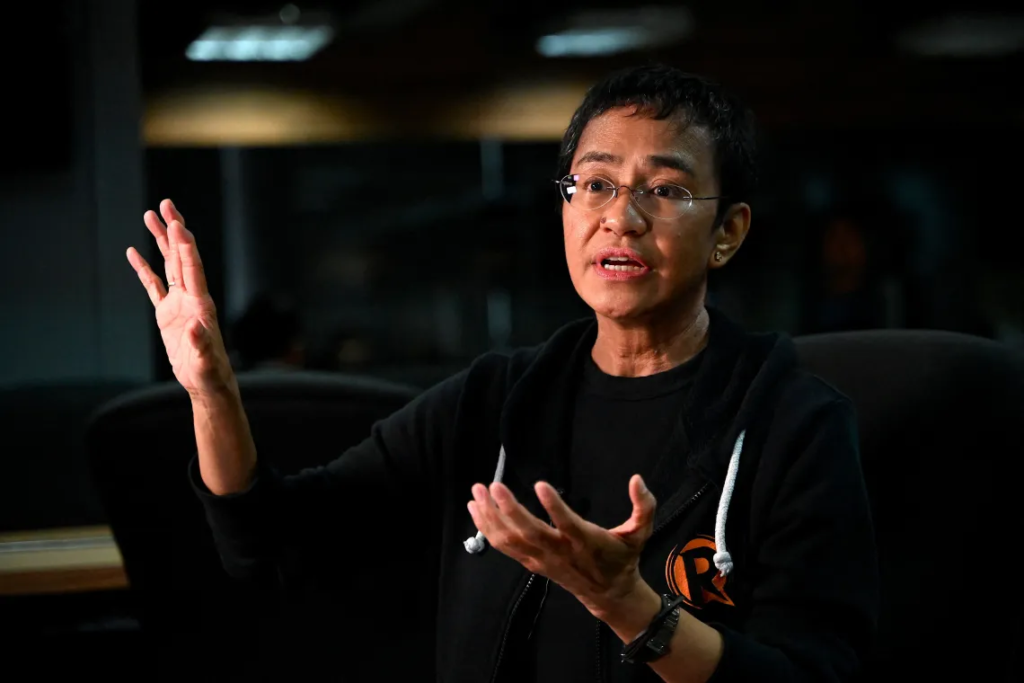

In an effort to deter the legal persecution of trailblazing journalist and Nobel Laureate Maria Ressa and her former colleague Reynaldo Santos, and to protect the public’s right to be informed, three leading civil society organizations, have submitted an amicus curiae brief to the Supreme Court of the Philippines.

The brief was filed on June 13 by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), the International Center for Journalists (CFJ) and Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in partnership with Debevoise and Plimpton LLP. It argues that the criminal convictions of Ressa and Santos for “cyber libel” not only breach the international obligations of the Philippines but betray a press freedom legacy the court has reaffirmed for more than a century.

The charges in this case relate to a 2012 investigative story published by Ressa’s online news outlet, Rappler, about businessman Wilfredo Keng and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, who was seen using a car that allegedly belonged to Keng. After Keng filed a libel complaint against Ressa and Santos in 2017, the journalists were criminally charged and eventually convicted by a Manila trial court.

In recent years, Ressa, her colleagues, and the online news outlet Rappler have faced a sustained campaign of legal persecution and online violence, with 23 individual cases opened by the government against them since 2018. Ressa and Santos face close to seven years in prison if their convictions for cyber libel, which are currently in the last stage of appeals before the Philippine Supreme Court, are upheld.

“Twelve years since the publication of an article that has been woven into a vicious campaign against Maria Ressa, Rappler and other members of the press, it is clearer than ever that this spurious case intended to silence independent, critical reporting simply does not stand. We urge the court to overturn the unjust convictions against Ressa and Santos. This weaponization of the law must come to an end,” said CPJ, ICFJ and RSF.

Citing international law and domestic precedent, the brief argues that this case and the Philippine government’s criminalization of defamation is misaligned with current best legal practices and incompatible with international law:

In short, journalists are unable to do their jobs under the Damocles’ sword of criminal liability. They have a duty to satisfy the public interest in being informed of public affairs, and must make daily and expeditious judgment calls about what information to report with an inherently limited set of facts.

The prospect of facing criminal liability for allegedly misreporting facts—or worse yet, being punished for accurate reporting—will have a profound chilling effect, discouraging journalists from wading into the sensitive topics that often are the subjects of greatest public concern.

This, in turn, undermines the public’s right of access to information and erodes freedom of expression more generally—costs that are hugely disproportionate to the interest the libel charges are ostensibly protecting.

This brief, if admitted by the Court, would be the third amicus curiae intervention accepted in this case, following filings by the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression and the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute in Ressa’s final appeal of her libel conviction before the Supreme Court of the Philippines.